Building IMOCA 60 11.2 Part 1: The Design Challenge

Guest author Mark Chisnell has written a three-part article series about our new IMOCA 60 ‘11.2’. In part 1, he explores the multiple challenges our team faced when building the boat.

It was a little over twenty years ago that the Swiss sailor Bernard Stamm and three crew blasted across the Atlantic on the front edge of a winter storm, and set a new monohull record for the New York-Lizard crossing of 8 days 20 hours and 56 minutes. They did it in Stamm’s IMOCA 60, beating a record that had been held by Bob Miller’s superyacht Mari Cha III by over four hours. At 44.7m length overall, Mari Cha was almost two and a half times longer than the IMOCA 60 and the new record spoke volumes for the future.

A possible future: an IMOCA 60 with four crew could have been the replacement for the aging Whitbread 60, the boat then used for the Volvo Ocean Race. The IMOCA 60 could have slashed crew numbers (and therefore cost) and ramped up performance and spectacle. Surely this new record was the harbinger for a remarkable future for offshore racing? Well, it’s taken 20 years, but the future is finally here, with the launch of 11th Hour Racing Team’s new IMOCA 60 – the first to be purpose-built for a four or five man crew. Personally, I can’t wait to see what she can do – and not just on the water. This boat was built with more than just speed in mind.

“The primary objective of 11th Hour Racing is to change the narrative around sustainability in the marine and maritime industries, and in everyday life. We start the conversation with the springboard of competitive professional sailing, then provide concrete solutions or demonstrations of achievable success, in the hope of alleviating some of what can be a daunting proposition to engage with from zero.”

Those are the words of Rob MacMillan, co-founder and President of 11th Hour Racing, the Newport, Rhode Island based organization which harnesses the power of sport to inspire ocean health initiatives, and sponsors 11th Hour Racing Team.

The IMOCA 60 is now used in the planet’s most popular and most visible offshore sailboat races; the fully-crewed Ocean Race (heir to the Volvo Ocean Race), the double-handed Transat Jacques Vabre and the solo Route du Rhum and Vendée Globe. Millions of people watch these races, and that means millions can be impacted by the message of 11th Hour Racing. Unfortunately, building a boat to the current IMOCA 60 rule has significant challenges when sustainability is your avowed goal. “The carbon is not sustainable, and the resin we use is not sustainable…. A carbon boat made out of pre-preg epoxy is not fantastic in this respect,” said Guillaume Verdier, the project’s naval architect, reflecting on the challenge facing the Team.

“I’d be very enthusiastic,” Verdier continued, “to try to design a boat that is really more sustainable and competitive. If I were free to write a rule, if I was asked to make a wooden Open 60, I promise you it would not be a piece of rubbish. It would be hard to compete [with existing boats]. It would need everybody to have a wooden boat, but… we’ll find the tricks, I tell you. If it was to be specified, we’ll find the tricks. Wood is a beautiful way [to go].”

“Make no mistake, we have to make radical changes to how we work: business as usual is no longer an option,” added Damian Foxall, 11th Hour Racing Team’s Sustainability Program Manager and a previous winner of the Volvo Ocean Race. “There is an urgent need for the entire marine industry to align to the Paris Agreement; a 50% reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, and net zero by 2050. This requires a paradigm shift in how and why we build and race boats; a new approach to sailing events and the very structure of our sport.”

After all, the sport of sailing is what we, the participants, say that it is; the boats, the racecourses, the materials used. But while wood would be a vastly more sustainable material, the IMOCA 60 rule currently allows carbon and so, if you want to win races, that’s what you need to build in. This is a fact that Mark Towill, the Team’s CEO is very conscious of: “With the support of our sponsor, our philosophy around the build of our new IMOCA 60 is to construct a competitive boat while working with the marine industry to develop more sustainable solutions and innovative approaches to the way that we build boats. We’ve already seen changes to the IMOCA Class rules including favoring the use of bio-sourced materials for non-structural parts and introducing life cycle assessments for the construction of all new boats, which is a great start and we look forward to working with more race organisers, Class owners and teams to push this agenda further. We hope that what we develop and learn with our partners can then be used as a springboard, not only within Grand Prix racing, but across the sector as a whole.”

“We’re only going to be able to do that [50% reduction] with real collaboration, making sure that we’re working in targeted areas and working together,” said Sustainability Officer Amy Munro, an oceanographer by training who works with Foxall. Together they implement sustainability measures throughout all operational elements of the Team. The goals have been set by international agreements (currently the 2015 Paris climate agreement). “The UN Sustainable Development Goals are not just for the marine industry, it’s everyone who needs to get to that point… And a lot of countries have ratified those targets. So it’s going to involve not just offsets but really looking at how we’re making things and how we can radically rethink to reduce our footprint,” added Munro.

Public opinion is inexorably shifting and sailing needs to shift with it. It may not be long before a sport that flouts climate targets will find itself as handicapped commercially as those that were – in an earlier era – reliant on tobacco sponsorship when public opinion and lawmakers turned against it. Sailing can do more than just keep up though, as Rob MacMillan explained. “The Ocean Race is an opportunity to carry this narrative message across the world and engage on local terms with many different communities. Especially now with the introduction of the IMOCA fleet into The Ocean Race, there is an exciting development opportunity as well, where teams can embed sustainable choices from day one.”

Changing the narrative is going to require more than just building a boat in the most sustainable way possible – that boat is also going to have to be successful in a harsh and highly competitive environment. To put it brutally; no one will be listening to the message if the boat is slow. So, in the first two stories in this three-part series we’ll look at how the Team went about designing a fast boat. Then we’ll turn, in the third article, to the challenge that the Team faced building it as sustainably as possible.

In the hot seat

Bearing much of the weight of the responsibility for these twin goals are two men, the first of which is 11th Hour Racing Team’s skipper Charlie Enright, who told me:

“For better or worse, the design and build process stops and starts with me.” Enright grew up sailing in Bristol, Rhode Island, U.S., and the sport runs in his family; his grandfather was a boat builder. He followed a path through junior sailing, interscholastic sailing, and then got into offshore racing through Roy Disney’s Morning Light project and, “never turned back. We did a lot of our own sailing in 2011, which is what introduced me to The Ocean Race. Mark [Towill] and I have done two laps of the planet now, and are very much looking forward to our third.”

The second person in the hot seat is the naval architect commissioned to come up with the design of the team’s new IMOCA 60, Guillaume Verdier. If you follow the French offshore scene then you may well know all about Verdier’s Vendée Globe-winning IMOCA designs, but if you don’t then you probably know of his collaboration with Team New Zealand over the last three America’s Cup campaigns, two of which they have won. After studying naval architecture at Southampton and Copenhagen Universities, Verdier joined Groupe Finot. “Designing Open 60s when I was 27 years old.” He worked on the boat in which Michel Desjoyeaux won the Vendée Globe, before going out on his own and modifying PRB for Vincent Riou, who also then went and won the Vendée Globe.

There were lots more winners, until recently designed in collaboration with another famous French design office, VPLP. Both François Gabart’s Macif, Vendée Globe winner in 2012-13, and Armel Le Cléach’s Banque Populaire which won in 2016-17 were designed in collaboration with VPLP. “Yannick Bestaven was the one that won the last Vendée Globe, [that] was a boat we did with VPLP, but Apivia [sailed to second place by Charlie Dalin] is a boat I designed on my own,” said Verdier.

It was Verdier and VPLP that got the IMOCA 60s foiling, and the experience that Verdier gained in the last three America’s Cups (all of which have featured foiling boats) has played into his hands as the IMOCA 60 rules have continued to allow foiling to develop. There are very few yachts that are built with no constraints, and for racing boats the primary parameters are the rules that define the type of boat. The IMOCA Class Rule started out simply enough back in the mid-1980s, but these days the designer of a new IMOCA 60 faces significant constraints.

IMOCA Class Rules

There are obvious limits, like hull draft and length, along with an air draft and an overall length that includes the bowsprit. There are also one-design elements; a mast and keel fin that limit the amount of righting moment the boat can develop, so there’s a point beyond which more power will simply break the boat. There are also limits on appendages, water ballast and canting keels along with all important self-righting tests. So it would have been simple enough to discourage foiling with a rule change if that’s what the rule makers had wanted.

This hasn’t happened, but nor has it been encouraged by allowing elevators on the rudders. While these add complexity and cost, Verdier feels they would significantly increase the boat’s fitness for purpose and safety. “The fact that you don’t have the elevators on the back of the boat is making the boat very brutal in deceleration. It’s an incredible damper [shock absorber] to have an elevator on the rudder. Maybe draggy sometimes, but it is the safety element…” The extra control the elevator provides for the trim angle of the boat would make it safer. “I tried to explain that to the IMOCA but they didn’t vote for [it]. That’s the way it goes. I’m not a good lobbyist,” he explained, with a wry smile.

All these rules provide a hard edge to the design envelope, while all the boats built – particularly the 14 foiling boats from the past two Vendée Globe races – provide a softer envelope, a wealth of knowledge on what works and what does not.

There is no shortage of history to draw on, but in one important respect, the new 11th Hour Racing Team boat is a very different one to all that have gone before because it was designed for a crew, and not just for solo sailing. A fully-crewed boat can be pushed much harder, so it needs to be stronger. There needs to be more space to live and different systems to allow the extra hands to work at sailing the boat.

Mark Chisnell, Author

Verdier Design Studio

Verdier has an edge on the competition in thinking about these issues. The first time I met him was in Lisbon, when the Volvo Ocean Race design team that he led were working on the Super 60, the brainchild of then-CEO Mark Turner. “When Mark Turner decided to make a new kind of boat after the Volvo Ocean 65, he made a giant competition,” Verdier explained. “We won that one, and started working with Nick Bice, Neil Cox and Mark Turner on this Super 60 program, and right away it was like an Open 60 that was adaptable to a group of five people on board. That’s where we are more or less today with this boat for The Ocean Race.”

When Verdier says ‘we won that one’ he’s referring to the team of people that he has gathered around him since he first went out on his own. “The original people are still here. It grew up a little bit, but we are more or less five or six in France.” The collaborators on this particular boat (and it varies from project to project) were Hervé Penfornis in project management, Romaric Neyhousser, designer, Véronique Soulé and Romain Garo doing computational fluid dynamics (CFD), Morgane Schlumberger working on structures and stability, Loic Goepfert working on performance and design and Jeremy Palmer working on structures. “And there’s the Pure Design and Engineering office for structural calculations in New Zealand. Matrix Applied Computing is also in New Zealand, doing the double check of the structure I’m doing for the foils,” added Verdier.

The team has always worked in a way that a lot more of us are now familiar with, thanks to Covid-19. “I sign the contract and so on, and it’s my name and I take the risk, but all these guys have their own design studio, in a way, like me, and they all accept to collaborate with me. It’s a very nice setup we have and very rare, where people are all independent. We all work from home. There’s no office. You don’t open the door of my office, see a secretary and 20 people working. Everyone is on their own, but we collaborate at a distance.” This is a lot more sustainable way of working than maintaining a big design studio and getting everyone to travel there every day.

The team also understood that the digital design process has its own environmental impact. “The thing we did on this project, and it has been the first time I’ve seen it, is to fully evaluate the carbon footprint right from the beginning, including the computer time we used for the process,” said Guillaume Verdier. “It’s not easy to work out how much time we spend, how many machines we have, how many clusters we use and so on, but we did better on this one.”

“There’s a growing impact of the digital sector worldwide,” pointed out Damian Foxall, “estimated at 3.5% of global GHG emissions or the equivalent of the entire aviation industry. More importantly, the global impact of digital use is set to increase by up to 14% by 2040, underlining the importance of understanding these impacts and using these tools and the associated energy needed responsibly.”

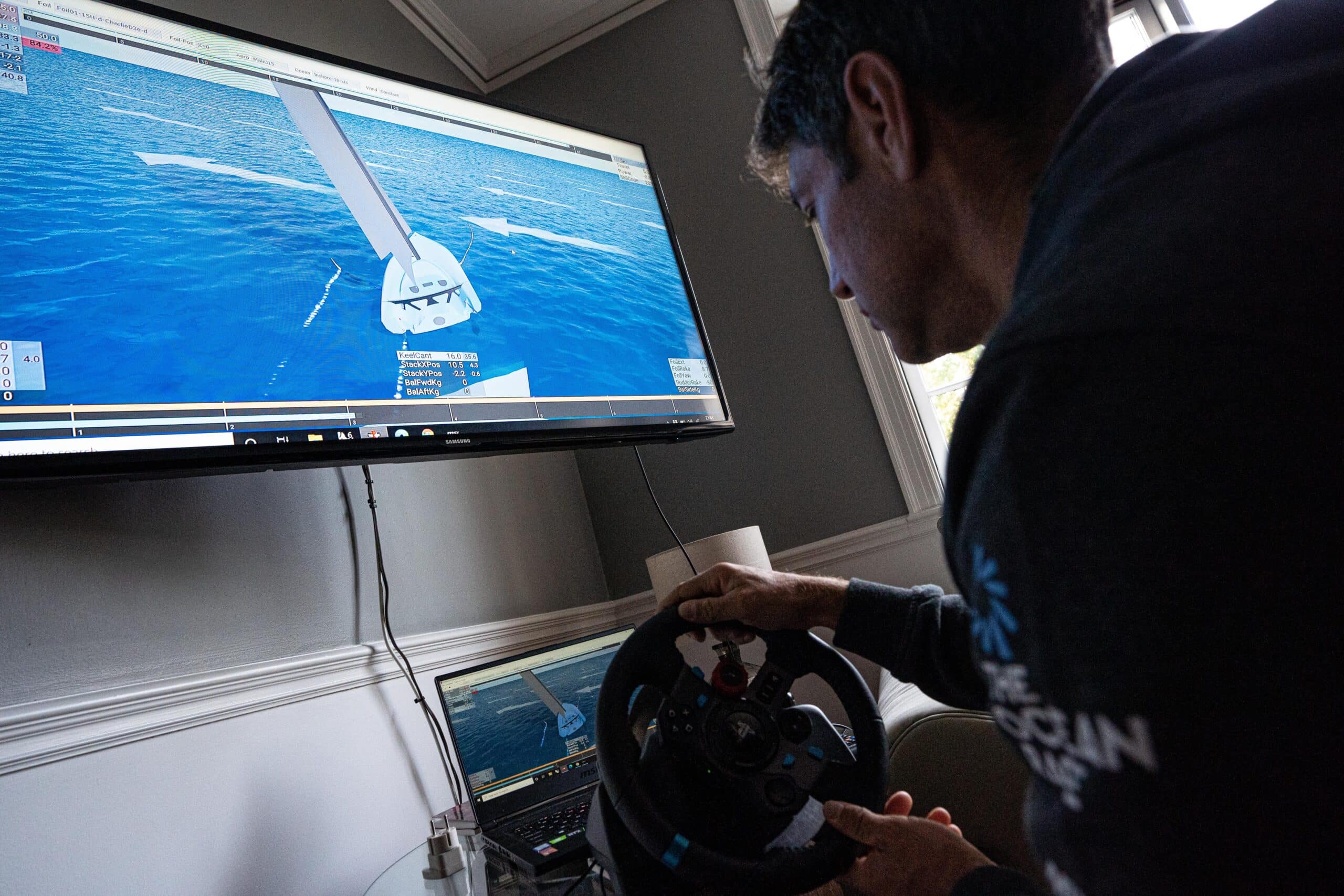

Simulator Training

One of the first problems that Verdier and his team had to tackle was the one big difference between the Super 60, and the IMOCA 60 that they were now designing for a full crew. “The Super 60 originally was designed to have elevators on the rudder,” said Verdier. “Again, I often say when you don’t have the elevator on the rudder, it’s a bit like trying to make your plane fly without the tail wing, which is very difficult.” The fundamental instability that this produces in the boat’s balance had to be resolved in other ways.

Verdier and his team have built up a significant toolset to apply to the problem, most notably the development of simulation codes. “A boat is a lot more complex than a plane though,” said Verdier, “because it’s got to go through an incredible change in pitch, an incredible change in displacement through the waves. It’s jumping waves and going down the troughs. It’s very unsteady. A plane is much steadier. It’s much easier to make a simulation for a plane or a car.” It’s a double whammy really, not only is an IMOCA 60 in the Southern Ocean harder to simulate than a plane, it’s also less controllable without the rudder elevators.

“We are progressing,” continued Verdier. “We have a simulator, and we can train on the simulator. We can add waves, but you always keep in mind that if the simulator is not answering the question perfectly, then reality is still driving the bus, you know? It should not be the tool that drives the bus, but your understanding of the environment. That has always been our job. Otherwise we’d be replaced by machines.”

Charlie Enright had the same take on the problem. “We have used the simulator a lot in the development program for the boat. The simulator’s definitely a useful tool because it highlights areas you might not otherwise be thinking about, and it allows you to make a lot of changes rapidly in a cost-effective way. It points the arrow towards things that could be investigated further. That said, it’s a lot easier to simulate flat water behind Rangitoto than it is the waves of the Southern Ocean, so it’s a constant back and forth between sailor input and the naval architecture simulation tools. It’s definitely a give and take, because we feel like we have the smartest guys in the world helping us design this boat, but at the same time, no two waves are the same. So the sailor input is very important, and I feel like we’ve struck that balance well to date.”

Striking that balance has led to some innovative solutions to the performance challenge, with a new look to the bow shape and foils, the aerodynamic treatment of the hull and the sail handling solutions just some of the more obvious changes. We will look at all these and much more in the second part of this three-part series.